Hello Substack!

So here goes - first time pressing the ‘publish’ button on Substack and here I am.

I have no real idea how Substack works, but I’ve been hopping from foot to foot on the sidelines for most of 2024, quietly watching others publishing their writing, enjoying the camaraderie of the intermingled gardeners, foodies, permaculture people, cooks and slow readers in the Substack community and sharing a few photos on chat threads run by others.

Thanks to the inspiration of many of you here, it is way past time to plunge the spade in and break ground.

What am I doing here?

This will be a Substack about growing mainly edible plants on an allotment (as these small scruffy parcels of land are known in the UK), or a community garden (for the US folks), and the practice of growing plants over time.

Allotments always have something to say, although they speak quietly and in different languages. (We’ll get to the diversity and multiculturalism of the whole affair in later posts.) I’m here to share the stories of my allotment community and how we grow together.

As I get more organized about things and more Substack-savvy, I’ll share what we’re sowing and planting, what’s growing in season, what’s being harvested and eaten and what we’ve made with the produce. Preserves and fruit-laden booze will certainly feature. There may be cake.

Where’s the action?

I grow on a traditional 10-rod allotment in Walthamstow in north-east London. In the spring it looks like this, when all the daffodils come up at once.

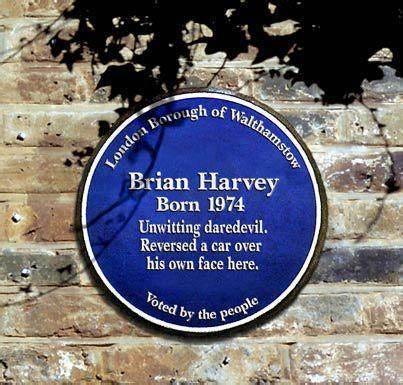

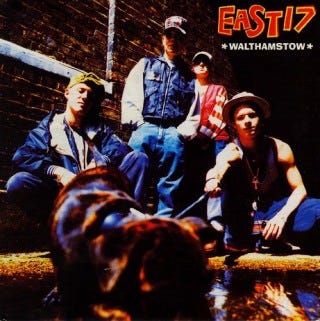

Walthamstow is north-east by London’s geography, east by the E17 postcode and firmly Out East (as opposed to Up West) by its character. In the 1990s E17 was only famous for having spawned a pop boy band, whose members were local to the area and whose 1993 debut studio album was titled ‘*Walthamstow*’. East 17’s lead singer, Brian Harvey, is now perhaps more famous in the ‘Stow for a self-inflicted injury caused by running himself over in his own car allegedly while eating a baked potato. The event is marked by several unofficial blue commemorative plaques in the local neighbourhood.

Walthamstow has gentrified enormously over the time I’ve lived here. Regular East End boozers with beer-sticky carpets have turned into would-be gastropubs or trendy craft beer microbreweries. What used to be an affordable, slightly scruffy area for ordinary folk to live in now has eye-watering rock star house prices, developments of posh apartment blocks sprouting up everywhere like nettles and a steady stream of builders’ skips in its streets as old Victorian terraced houses acquire designer loft and kitchen/dining room extensions.

I’m sometimes surprised that the borough’s allotments have survived and have not been built on by property developers hungrier for profits than for handfuls of fresh raspberries or a squeaky spring cabbage.

Welcome to the plot

My plot is measured in the traditional British Imperial measurement of rods.

A 10-rod plot is 1/16 acre, 300 square yards or roughly 250m2 in metric but measurements on allotments are rough and ready – most allotment sites have gradually lost over time any precision they may have had when the individual plots were laid out. Boundaries change as plots are divided, brambles grow up on the common paths and nature refuses to observe straight lines. I’m lucky that all four boundaries of my 10-rod patch are clear and uncontested. On the main shared path to the south, there’s an ancient cherry tree on one corner which probably dates to the site’s enclosure as allotments in 1850.

To the north, the border path has always been less clear, as it doglegs between plots of different sizes at their backs, which otherwise line up in a straight line at the front. There were no obvious markers when I took on the plot except an almost-straight row of overgrown fruit trees (two bird cherries, one bent-over Victoria plum), and an old compost bin made of rotting wooden pallets. The compost bin collapsed several years ago, and I’ve now got a row of horticultural pots where bulbs and perennial flowers wait their turn out of season.

A 10-rod plot is considered a ‘full size plot’ in our borough and the 10 square rod size was historically intended to be the size of plot needed to produce sufficient vegetables, fruit and flowers for the plot-holder and their immediate family. Food year-round for four to six people then. Rabbits were also kept on allotments for food during World War II, to supplement families’ meat rations.

Some allotment sites allow bee keeping (ours doesn’t, much to my ongoing disappointment), others permit runs for chickens and other fowl if the plot-holder is prepared to let their birds run the nightly gauntlet on land prowled by urban foxes. We have a lot of foxes on the site, many in a single extended family, which means I wouldn’t have chickens or ducks even if they were allowed. Plus, the foxes have names. They’re almost family and they keep the grey squirrel population down. (Fewer grey squirrels equals more baby birds hatching, as their eggs don’t get eaten, and more birds in turn eat aphids and other pests off the veg.)

Why do I do this?

What allotments, or rather the plants which grow on them, teach us is great patience over time, and patience with factors outside of a grower’s control. 2024 has thrown a long wet spring into the mix, with advancing battalions of slugs and snails munching everyone’s seedlings almost before they could get roots into the soil.

I was not happy that my one flourishing Ukrainian pumpkin plant was reduced to a sorry green stump over a weekend, but I still have some viable pumpkin seeds to grow again next year. (The seeds were shipped by land across Ukraine through war zones, so they’ve already been through a lot. I figure I should give the remaining ones at least a chance after all that effort just to get to the UK.)

Every day a grower learns through practice, turning the soil, sowing seeds, tending plants, pruning and weeding. Some efforts flourish, others fail completely. I have had plenty of failures but somehow each new growing season comes with new hope. If this summer’s climbing French beans do fail (and they’re not looking great, if I’m honest) I’ll replant next spring and go again.

As the East 17 boys would sing, a grower always gets to ‘Stay Another Day’.

These instalments are currently free to everyone, as I’ll not flatter myself that anyone will want to read my natterings, let alone pay for the privilege. Let’s see how this goes over time. (There’s something somewhere Substackers can press to sign up as potential founder subscribers when the time comes, but I haven’t found it yet.)

Expect photos of wonky vegetables, ramshackle sheds made of skip-shopped recycled materials and the odd urban fox.

Welcome to the ongoing garden party on Substack!

I am so pleased to discover you here and look forward to reading more of your allotment here!